Although the first clinically useful images created by magnetic resonance imagery were not used until the 1980s, the development of the technologies that contributed to the original and modern versions of the MRI machine began decades prior.

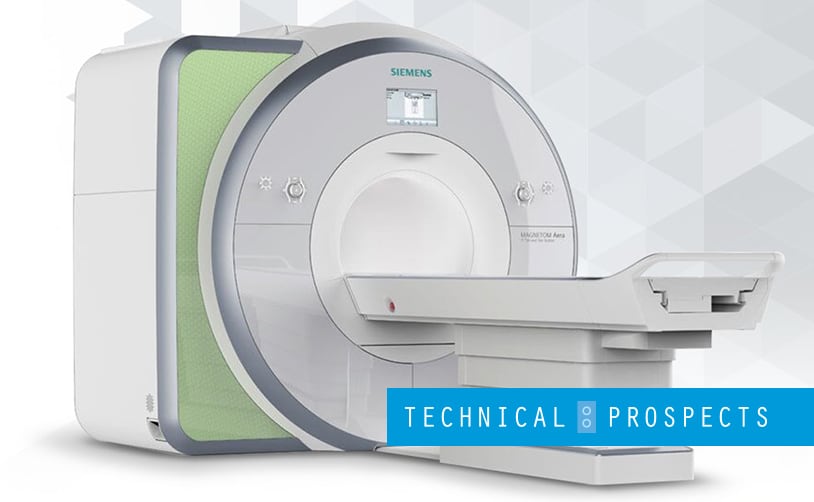

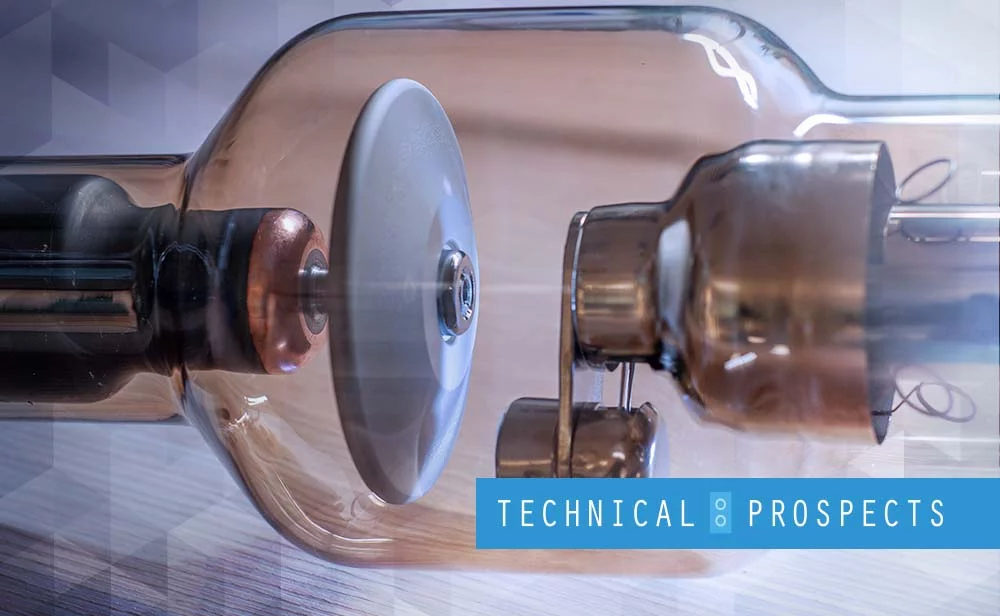

Magnetic Resonance Imaging, in layman’s terms, is a test that uses powerful magnets, radio waves, and a computer to create images of the inside of the body. These images are taken in “slices” and are used to diagnose illness or prepare for surgeries. Unlike x-rays, MRIs do not use radiation and are most often used to study soft tissues and the nervous system.

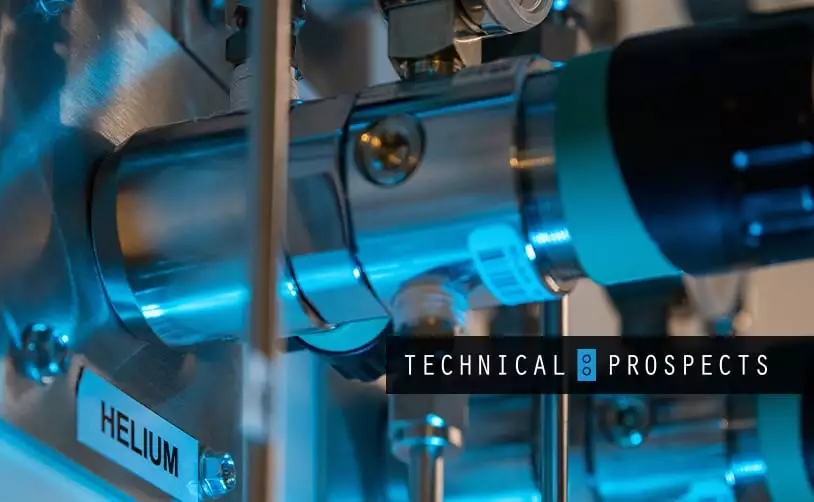

A functional MRI, or fMRI, is used to understand blood flow in the brain and to map brain activity. While undergoing an MRI of any kind, the patient lies on a platform that slides inside the “bore,” which is a tube open at both ends that encapsulates the body. While the patient lies still, the magnet moves around the body and forces protons in the body to align with the magnets. The time it takes for the protons to realign with the magnetic field as well as the energy released during the process tell doctors different things about the types of tissues they’re observing.

Developing the Science behind the MRI

Understanding the science behind the MRI helps us understand all of the scientific and medical developments that needed to take place before the modern MRI machine came to fruition. The physics behind Nuclear Magnetic Resonance, or NMR, was first understood and further researched in the early 1950s by Erwin Hahn. In 1952, a Ph.D. candidate named Herman Carr produced the first reported one-dimensional NMR spectrum as part of his thesis project. This would later be built upon in creating the modern-day MRI.

In 1960, the first patent was filed for a magnetic resonance imaging device, which bridged the gap between the NMR spectrum and the MRI imaging as applied to medicine. Vladislav Ivanov was the physicist behind this patent, although not the first scientist to fully expand on the idea. His proposal was that the magnetic gradient would reveal spacial details within the body.

Scientists Jay Singer, Alexander Ganssen, and others then began work experimenting with NMR technologies and studying blood flow and gradient anomalies within live patients and animal subjects, and in the 1970s, medical scientists discovered some abnormal NMR data associated with cancerous tissue. It was then that the medical profession began work to develop the MRI as a mechanism by which cancers and other tumors could be seen and studied.

Throughout the late 1960s and early 1970s, multiple patents were granted for various types of NMR scan machines that attempted to identify and study cancer and other growths within the body. However, none of the scientists who theorized that these types of machines would be impactful were able to successfully develop the mechanisms by which scans could be done, both safely and effectively.

The first MRI machine

The first nuclear magnetic image was published in 1973 by Paul Lauterbur. Lauterbur was able to expand on the work of many scientists before him in order to produce images in both 2D and 3D, however, they were lacking the clarity and timeliness that were required for practical patient applications. His ideas were further expanded upon by Peter Mansfield, who in the late 1970s developed the echo-planar imaging technique that improved on both image quality and scan time. The first MRI body scan of a human was produced on July 3rd, 1977 by Raymond Damadian, Larry Minkoff, and Michael Goldsmith. Damadian claimed credit for inventing the MRI.

The Evolution of the MRI

The first full-body MRI scan machine was developed by John Mallard and his team at the University of Aberdeen throughout the late 1970s. This machine was used to produce the first “clinically useful” image of a patient in 1980. Although many scientists were working on the development of the MRI, this was its first successful, pertinent application in a clinical setting.

This same machine was used in St. Bartholomew’s hospital in London from 1983 to 1993 and is credited for the widespread availability of MRI equipment throughout the world. Later advancements employed stronger magnets as well as heart and brain-specific imaging in order to study these parts of the body.

The use of contrast agents, like gadolinium, helps provide greater contrast on some types of MRIs. Although the science behind the contrast agents, which is given intravenously, is credited to Paul Lauterbur, they were not used clinically until 1988. The beginning of the development of the fMRI, which uses oxygen-depleted blood, began in 1990.

Who is Credited for Inventing the MRI?

In 2003, Sir Peter Mansfield and Paul Lauterbur were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for their work in developing the MRI as we know it today. However, we also give credit to the contributions in science and development of concepts to Raymond Damadian and the work on NMR technologies to Isador Rabi, Felix Bloch, and Edward Purcell years prior.

Paul Lauterbur’s credited contribution was in projectional NMR tomography, which shows a slow in proton spin-lattice relaxation time at a rate that varies between different tissues. Lauterbur used a series of one-dimensional images paired together to create a 2-dimensional image of the specimen. He first produces a 2D image of a clam using successive 45-degree rotations of the one-dimensional images and mathematically “back-projected” them to complete the image.

Peter Mansfield is credited with using “slice” imagery and magnetic field gradients to develop a more 3-dimensional image of the specimen. Mansfield and his colleague, Andrew Maudsley, later revisited and refined this technique in a “line scan” technique to create the first magnetic resonance image of a human finger in 1977.

Ramond Damadian is credited for his ideas for a full-body scan machine, which is what we recognize as an MRI scan machine today. His motivation for the creation of such a machine was the hope of a fast and non-invasive means of diagnosing disease within the body. His company, FONAR, was the first to manufacture clinical MR machines and was named after his imaging method, “field focused NMR,” which moved the patient in a rectangular pattern to obtain images from all pixels. Despite his contributions to the creation of the modern MRI, Damadian was snubbed from the Nobel Peace Prize and felt this was a personal injustice, as did many others.

Today’s MRI

Since the invention of the modern MRI machine and its widespread distribution and use in clinical settings, a number of advancements have been made to improve its function. Key research surrounding the use of contrast agents has not only proved their effectiveness but made MRIs safer for specific populations who may have physiological reactions to these agents. Those with end-stage renal disorders are recommended to forego MRI testing with contrast agents. Several more agents have been developed and implemented in standard MRI use for reasonably healthy patients.

Advances in imaging of the brain and central nervous system have improved the testing process for patients with neurological concerns. The use of certain contrast agents allows doctors to see both blockages in blood flow and disruptions in the blood-brain barrier associated with tumors and other abnormalities. CE-MRI provides information about the size, location, classification, and grade of lesions, if any, identified by images produced, which can help diagnose stroke, MS, blood supply issues, and damage to the brain. The MRI is currently the standard test used to diagnose MS in new patients.

Magnetic Resonance Angiography, or MRA, is a function of magnetic imaging that looks at the heart and blood vessels. MRAs and cardiac imaging are two advanced uses of the MRI that allow a less invasive and radiation-free look at the functions of the cardiovascular system in patients with known heart defects and anomalies. The MRI is also used to image portions of the body that include the breast, abdomen, and musculoskeletal system to diagnose both injury and illness.

The Future of the MRI

Currently, MRI use has been proven to be a safe, effective, and non-invasive, more convenient way of approaching patient diagnosis and treatment. The MRI continues to develop as technology does, bringing more clear and complete pictures to medical facilities with slice counts as high as 128, 256, and beyond. Imaging times have also been cut way down.

Patient comfort has also been prioritized, as many patients experience acute anxiety when undergoing MRI testing, especially patients who are or may become claustrophobic. Larger bore sizes mean more space within the MRI tube, where patients are now able to hear music play through headphones while the machine scans are taking place.

Compressed sensing and Bayesian iterative reconstruction methods are exploring the use of k-space data to create complete 3-dimensional pictures from relatively fewer measurements. Medical scientists hope to develop this further to create shorter and even less invasive patient experiences. As the MRI is relatively new, more experience with contrast agents will allow for dosage and type selections that are more informed in the future than currently used best-practices.

Although magnetic resonance imaging is a relatively new technology, it has proven effective and instrumental in the treatment and diagnosis of dozens of common conditions. As its technology continues to improve, there’s no doubt that the MRI will remain a necessity in medical facilities throughout the country and world for decades to come. Its use of magnetic fields, and not radiation, make it the preferred choice for many doctors, and a safer alternative to the x-ray for most.

If you’re looking to purchase an MRI machine, feel free to reach out to DirectMed Parts & Service for a quote.